Robert E. Olson

Era: Korea

Military Branch: Marines

Photo 1: Duluthian Bob Olson is shown in spring 1951 during his service in Korea, where he was a member of the Marine Corps’ First Division. He is wearing the Navy and Marine Commendation Medal with Combat V, which he had just been awarded for actions at the Chosin Reservoir on Dec. 8, 1950.

Photo 2: Mr. Olson at age 16 in uniform.

Photo 3: Mr. Olson with friend at English Legation, Peking (Beijing), China, 1946 or 1947

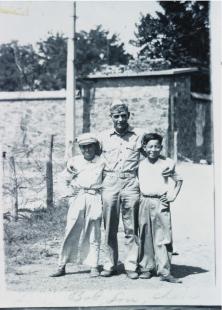

Photo 4: Mr. Olson with Chinese houseboys Lou and Chan, 1946

Mr. Olson served in World War II and in the Korean War.

He served in the U.S. Marines. He was inducted on March 22, 1946. He was discharged in 1962.

In World War II, Mr. Olson served in the F Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine, 1st Marine Division in China.

When the Korean War began, he was part of B Company Marine Reserve Unit out of Duluth, Minnesota. He served in the A Company, 1st Battalion, 7th Marine, 1st Marine Division in Korea. He survived the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

Mr. Olson was born in December 1929 in Duluth, Minnesota, the son of Ted and Mae Olson.

Mr. Olson was decorated with the Navy and Marine Commendation Medal with Combat V, the Combat Action Ribbon, and miscellaneous ribbons and medals.

------

“Duluthians in a Changing China,” Duluth Budgeteer, September 12, 2010

Confucius, China's most influential philosopher, once said, “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” His wisdom was heeded by two Duluthians who, separated by 60 years, visited Confucius' homeland and have vivid tales to tell.

In July, 1946, the U.S.S. General Breckenridge followed an American submarine up the mine-laden Yangzi River and docked in Shanghai, China. World War II was over, and America, fresh from the victory, was a newly emboldened nation. China, after years of military occupation by Japan, was being torn in two. The Communists of China regularly attacked the Nationalist government, and the outcome of their clashes was anything but certain. The Marines came to help the Nationalists.

The ship's officers disembarked in Shanghai, and the officer of the deck stood guard by the gangplank. The rest of the crew—the grunts—weren't allowed to go ashore. Onboard, sixteen-year-old Bob Olson and three of his shipmates waited for darkness to fall.

Once it was dark, they quietly stole across the deck and slid down the oil-coated cable that tethered the ship to the dock. They hid in an alley and changed into clean clothes. Then they headed off to see the town.

Bob had grown up in Duluth, another port town, but the Shanghai waterfront on a hot July night was a dazzlingly different world: crowded, exotic, and exciting.

On the streets, rickshaws and bicycle rickshaws zigzagged between pedestrians. Cars were a rarity. The four young American men were glad to feel land underfoot. In khaki uniforms, they stood out as they threaded their way through the crowds of men, women, and children, most of whom were clothed in floor-length garments or draped traditionally in long pieces of fabric, Bob remembers. Some carried loads on their heads, others shouldered wooden yokes from which hung heavy containers.

Bob and his companions had been given no cultural sensitivity or language training while on their way to China. They were treated graciously, and, adds Bob, “American money was well received.”

They spent the night wandering around the city, stopping at honky-tonks and exploring.

When the four young servicemen returned to the river the next day, they had no way to board the ship and stood helplessly on the dock scratching their heads.

The officer of the deck was surprised.

“Boy, oh, boy—now I've seen everything! You guys are something else!” He rolled his eyes and shouted, “Okay, come on up!”

Docked near and floating past the powerful ship were numerous sampans, the flat-bottom wooden boats that were a mainstay on the Yangzi in the 1940s. Sampan captains quickly learned to keep clear of the General Breckenridge, because her crew sank any that came too close with a high-pressure fire hose. It is telling that this rough use of American might was essentially left unchallenged: too bad, then, if you were the sampan owner. “I didn't think it was right,” Bob recalls.

The Americans weighed anchor and traveled north to Tanku. Bob and most of the Marines unloaded and traveled by land to Tangshan, a major hub of the Chinese coal industry. There Bob was a rifleman with an assault platoon.

Their unit was assigned to protect coal production and transportation from attacks by the Communists. They guarded the power stations that provided electricity for the mine pumps. (The pumps kept water out of the mines, where 5,000 men toiled, which otherwise would have flooded.) They also guarded the coal trains, standing in them and sometimes on top of them, as well as protecting the tracks and bridges along which the coal trains ran.

The Americans stayed in a vacated Japanese girls' school. Two Chinese houseboys, Lou and Chan, worked there. To Bob, they were like little brothers. (Years later, when Bob served in the Korean War and fought against Chinese soldiers, he wondered sadly if the two houseboys might have been among the men he fought in battle.)

Bob has fond memories of China. In addition to Tangshan, Bob served in Peking (Beijing) and elsewhere. His unit left China at the end of May, 1947.

Has he ever gone back? No—but he would like to . . .